COLUMN — On the first Monday of Advent, in the gold-domed capital of American Catholic respectability, a soft-spoken priest from South Bend walked into the Basilica of the Sacred Heart and picked a fight with the entire idea of throwing people away.

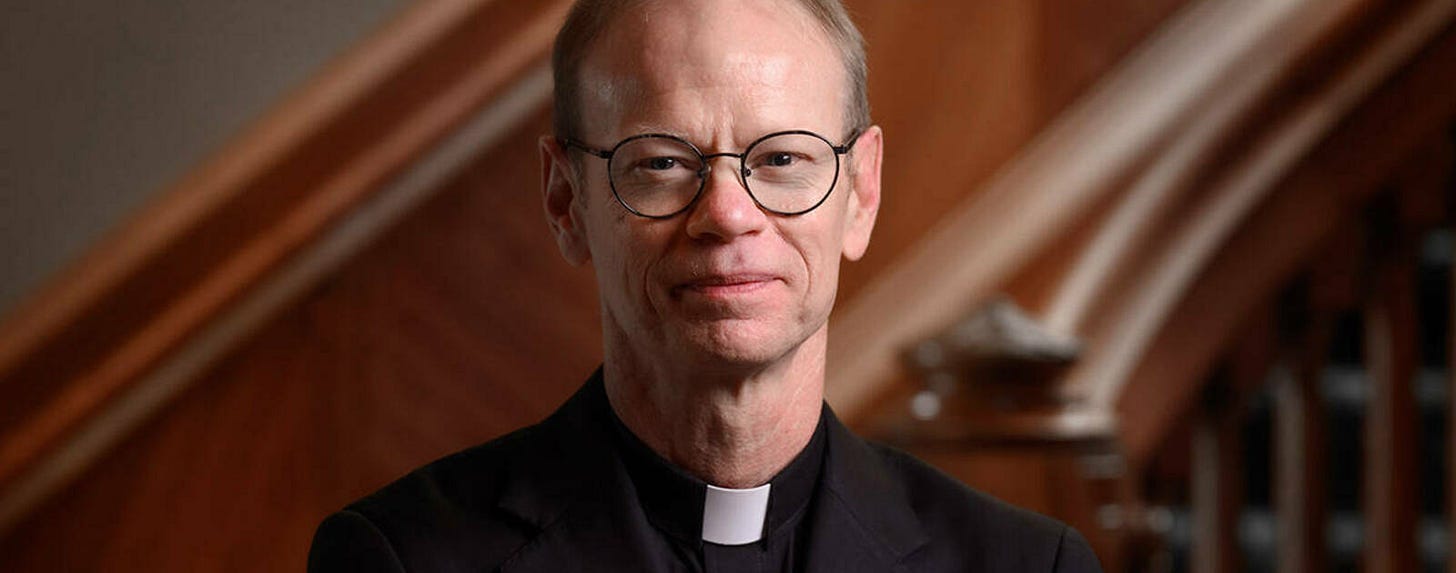

Father Robert A. Dowd, C.S.C. is not built for spectacle. He doesn’t boom from the pulpit. He doesn’t perform. He has the voice of a guy who would rather be at the back of the room, listening — which is how I met him.

Dowd was my priest-in-residence in St. Edward’s Hall when I was an undergrad at Notre Dame. If you were having the worst week of your life, you could crack open his door, sit down, and talk. He’d lean back, fold his hands, and let you empty the drawer.

One of the best listeners I’ve ever met. You’d forget, for long stretches, that under all that Midwestern low-key humility was a man who devoured political science texts for fun and spent his life figuring out how to help kids like us become the sharpest, freest, most decent versions of ourselves.

That same man is now the 18th president of Notre Dame.

So when he stood up on December 1 to preach a “Mass for Immigrants and Immigration Policy Reform” at the start of Advent, this wasn’t just another homily. It was Notre Dame’s new president putting his name — and the university’s — on the hardest moral question in American politics: Who counts as human when it’s inconvenient?

He didn’t start with Trump or JD Vance or the latest polling crosstabs. He started with Matthew.

You know the passage. The Son of Man comes in glory, separates the sheep from the goats, and judges the nations on one simple standard: how they treated the hungry, the thirsty, the stranger, the naked, the sick, the imprisoned. Most of us heard it growing up as a sort of spiritual checklist: feed the poor, visit the prisoner, don’t be a jerk.

Dowd tightened the screws.

In the Gospel, he reminded the room, Jesus doesn’t just say, “Be nice to the vulnerable.” He says, I am there. I am them. If you turn away the stranger at the border, you turn away Christ. If you terrorize families with raids, you terrorize Christ. If you build a system that strips people of dignity because their papers aren’t in order, you’re not just breaking a statute — you’re breaking faith.

He warned against turning God into an abstraction: an idea to admire instead of a person to face in flesh and blood. And then he told us exactly where that flesh and blood is standing in America right now: with people who crossed deserts and oceans, people living one knock on the door away from catastrophe.

This is not “both-sides” Catholicism. This is not the cautious, edge-walking style people got used to under his predecessor, Father John Jenkins, who spent years trying to keep Notre Dame out of partisan food fights and still ended up there anyway — first when Barack Obama came to give the 2009 commencement address, then when Amy Coney Barrett, a law professor from right down the road, joined the Supreme Court. Jenkins tried, God bless him, to live in that narrow strip between the culture war trenches. History shoved him into the crossfire.

Dowd is doing something different. He’s not waiting for politics to come for him. He’s starting where the Gospel starts and letting the chips fall.

And he’s not doing it alone. A few months before that Advent Mass, Pope Leo XIV — Francis’s successor — took one look at the Trump administration’s mass deportation program and lit into it with the kind of language popes usually reserve for war and famine.

Any doctrine of immigration built on force instead of the equal dignity of every human being, he told America’s bishops, “begins badly and will end badly.” Any theology that quietly equates “illegal” with “criminal” betrays the Christian story. He acknowledged the obvious — nations have a right to defend themselves, governments have tough jobs — and then said the quiet part out loud: mass deportation of people who fled poverty, violence, and environmental collapse is an assault on human dignity that leaves families “vulnerable and defenseless.”

The bishops treated that message like the emergency flare it was. It was only the second time in twelve years they’d issued a “special message.” The first was about the contraception mandate. This one was about the deportation mandate.

Dowd stood in the Basilica and said, in effect, Notre Dame is with that pope, that teaching.

Yes, governments have a right and responsibility to control their borders, he said. Yes, the system is broken and has been for years. But people who’ve been here for a long time, contributing to and enriching this country, must be treated with the respect their God-given dignity demands. Anything less — fear that keeps parents from taking kids to school, to the doctor, even to church — is a scandal.

Then he looked straight at the university he now runs.

“At Notre Dame,” he said, “we must do more than complain. We must deepen our understanding of the complexity of the situation and work with others to propose sensible and humane solutions. That is what universities are for.”

That sentence might be the real line of the homily. It sounds simple. It is not. It’s a mission statement.

Because if you know this place’s history, you know Dowd is plugging into a power source that’s been live for a century.

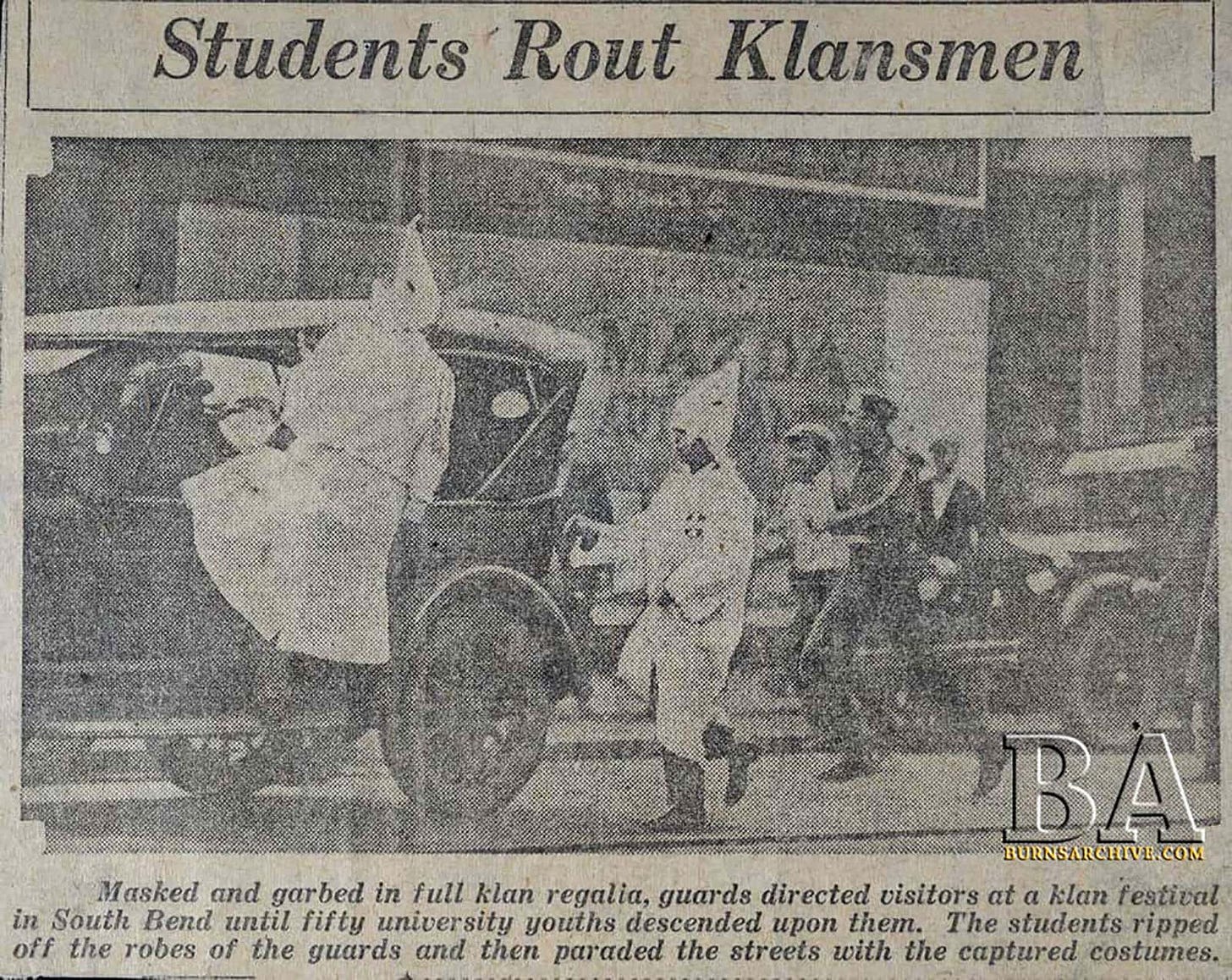

In 1924, when the Ku Klux Klan tried to stage a big rally in South Bend, they weren’t some online cosplay outfit. They were four million strong, woven into police forces, school boards, and city halls across the country. Their target that day was Catholics.

Notre Dame students — about 500 of them — didn’t issue a sternly worded statement. They ran downtown with bats and gardening equipment. They pelted a neon “fiery cross” with potatoes until the bulbs burst and the glass shattered. They charged up the stairs toward the Klan office and caught gunfire for their trouble. There was blood on the street. But the Klan’s grip on South Bend broke. “Fighting Irish” wasn’t a marketing slogan after that. It was a police report.

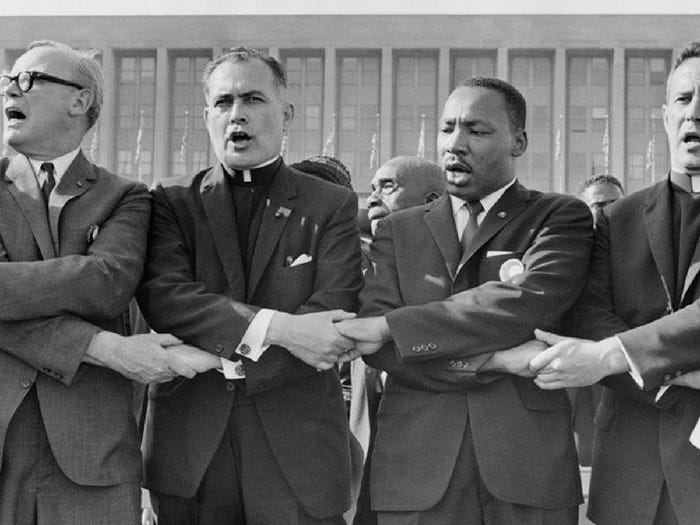

Decades later, another priest put on his collar and walked into the teeth of a different fight. Father Theodore Hesburgh spent fifteen years on the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, pushing, prodding, and infuriating presidents until one of them — Richard Nixon — finally kicked him off.

Before that, Hesburgh flew to Chicago and then to Selma when too many religious leaders decided the Civil Rights Movement was “too political.” He linked arms with Martin Luther King Jr. and sang “We Shall Overcome” under Southern sky. There’s a photo of it in a Smithsonian case now, but at the time it was just a Catholic priest picking a side.

Hesburgh called Notre Dame a lighthouse and a crossroads: a place that stands apart, lit up, and a place where people meet in the middle. Barack Obama quoted that line when he came to campus. The flattery was deserved.

This is the lineage Dowd is stepping into — not inventing from scratch, just dusting off and pointing toward the border.

What makes him interesting is that he’s not just a throwback moral voice. He’s a working political scientist with an almost nerdy hunger for data and argument. He did his grad work on how Christianity and Islam interact with democracy in Africa. His book argued that religious diversity, handled right, can strengthen liberal democracy instead of wrecking it. That’s not the sort of thesis you arrive at by shouting on cable news. It takes years of listening, counting, comparing.

Then he took that brain and built something.

In 2008, Dowd launched the Ford Program in Human Development Studies and Solidarity. If that sounds like a mouthful, here’s what it meant in practice: no more academic “drive-bys” in poor communities. No more parachuting into a slum, grabbing data, and vanishing back to campus. The Ford Program committed to sticking around, listening to local people define their own problems, and making sure research translated into concrete changes.

In Dandora, a slum in Nairobi, that meant confronting maternal death rates that wouldn’t let you sleep. Years of fieldwork on how poor women were treated in hospitals ended not with a stack of journal articles, but with a new hospital — Brother André Hospital — with a maternity ward built to treat poor women like human beings instead of statistics.

That’s the guy the trustees hired to run Notre Dame.

In his inaugural address, he didn’t just talk about “excellence” and “innovation” and other words that disappear into alumni brochures. He promised that every undergraduate — American, international, rich, broke — would have a shot at a Notre Dame education without drowning in loans. Loan-free. Need-blind. On a campus where tuition looks like a mortgage, that is not a small thing. That’s an institutional way of saying: poverty is not a moral defect and it’s not a disqualifier.

Put all that together and the Advent homily stops looking like a one-off “immigration Mass” and starts looking like the first chapter of his presidency.

He framed Advent as a season of holy eyesight. Can you recognize Jesus in the weak and vulnerable, he asked, or do you only look for him in the strong and respectable? Can you see him in an immigrant mother who’s afraid to take her child to a clinic because she heard there were ICE agents in the parking lot last week?

He reminded the room that Christian hope is not Hallmark optimism. The life, death, and resurrection of Jesus say pain, suffering, and death don’t get the last word. Love does. Not because Congress suddenly finds its spine, but because God does.

And then he borrowed a line from Pope Leo, who had just told a crowd in St. Peter’s Square that hope means taking a stand. Not a tweet. A stand.

Dowd translated that into Notre Dame terms: take a stand for the God-given dignity of every human life, from conception to natural death, including people without status or power or citizenship. Pray for immigrants. Push for humane policy. Respect the hard jobs of the people who enforce the law, but refuse to let “hard” become an excuse for “cruel.”

And for the university? “Do more than complain.”

Here’s what that sounds like: Notre Dame doesn’t get to be neutral on whether we cage people or disappear them. Not in 1924. Not in 1964. Not now.

The world outside the basilica will still talk about this as “the migrant issue” or “border security” or “the Latino vote.” The Trump people will talk about numbers. The JD Vance set will talk about “civilization.” Most of cable news will talk about the politics of all of them.

Dowd did something more dangerous. He talked about souls. Ours.

There is a real chance, if he keeps going like this, that his tenure will be remembered as the moment Notre Dame stopped treating immigration as a talking point and started treating it as a test of whether the place still has a conscience. A lighthouse is no use if it never points its beam at the rocks everybody’s crashing into.

The university has the tools: a law school that represents immigrants and asylum-seekers, scholars who can design policy that doesn’t confuse weakness with threat, a student body full of kids whose grandparents crossed borders with nothing but a suitcase and a borrowed jacket. It has a history of punching way above its weight in policy and politics.

What Notre Dame also has now is a president who spent his early years listening to terrified college kids at two in the morning, who built hospitals in Nairobi slums, who reads popes and political science with equal interest, and who just used his first Advent as president to say, plainly, that how we treat immigrants is how we treat Christ.

For a long time, when I thought of Father Bob, I thought of a guy in a modest room in St. Ed’s, asking questions and really hearing the answers. After Monday’s homily, I think of him in a different room — the basilica — asking the same question of the whole Notre Dame family:

Who did you see when you looked at the stranger?

Coming from one of the best listeners I’ve ever known, it’s not a question we can pretend we didn’t hear.

Follow us on Instagram.