WASHINGTON — History does not repeat itself, but it does endure the same recurring fevers. For two years now, I’ve painted the State of the Union from the upper gallery of what was once the House chamber, today is Statuary Hall.

As a migrant from Chile, it is an honor and a privilege to paint the portraits and landscapes of my beloved Congress. To walk through the Capitol corridors this week—past the heavy velvet ropes and the nervous glances of the new security details—is to be reminded that the war on the “foreign-born” is the oldest unfinished business in Washington.

Up in the West Wing, Stephen Miller, functioning now as the shadow president in all but title, is busying himself with the logistics of a purge. He is not merely interested in deportation, but in erasure—a scrubbing of the “migrant excellence” that he views as a stain on the national fabric.

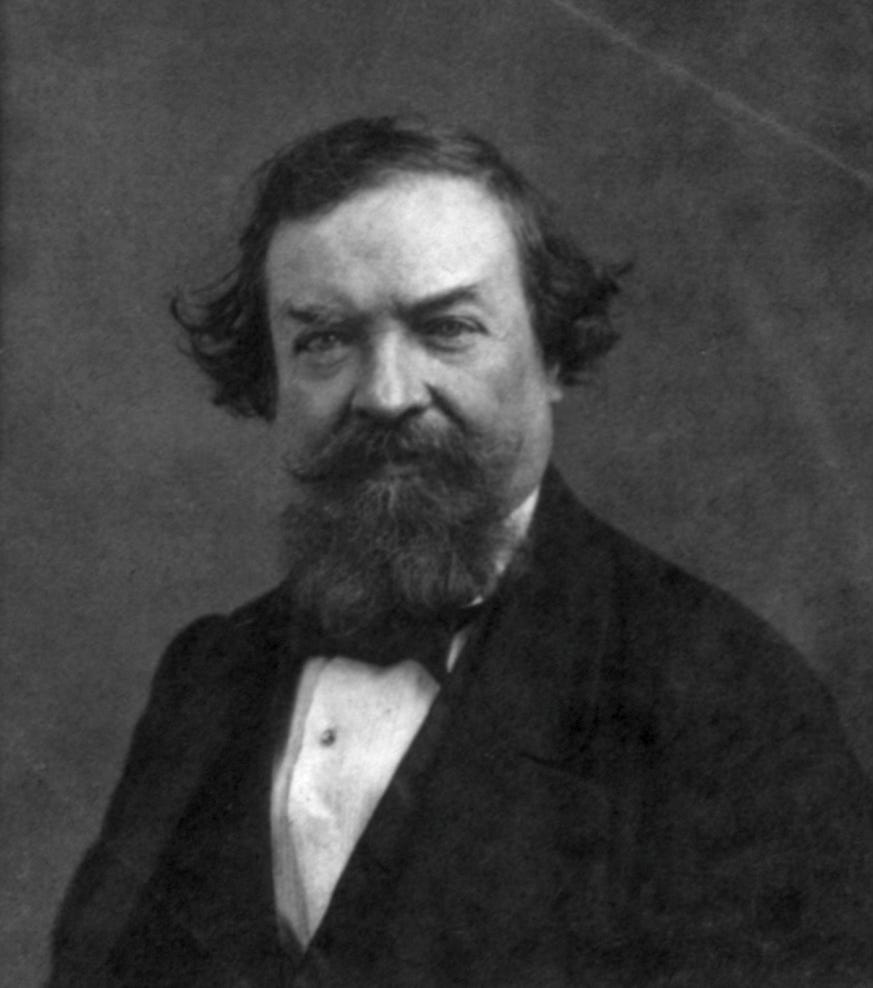

But if Miller were to actually look up from his manifestos and gaze at the ceiling of the very building where he once served as a Senate aide, he would find himself staring into the eyes of Constantino Brumidi, a Roman refugee who painted the soul of the American legislature while the Stephen Millers of the nineteenth century tried to starve him out.

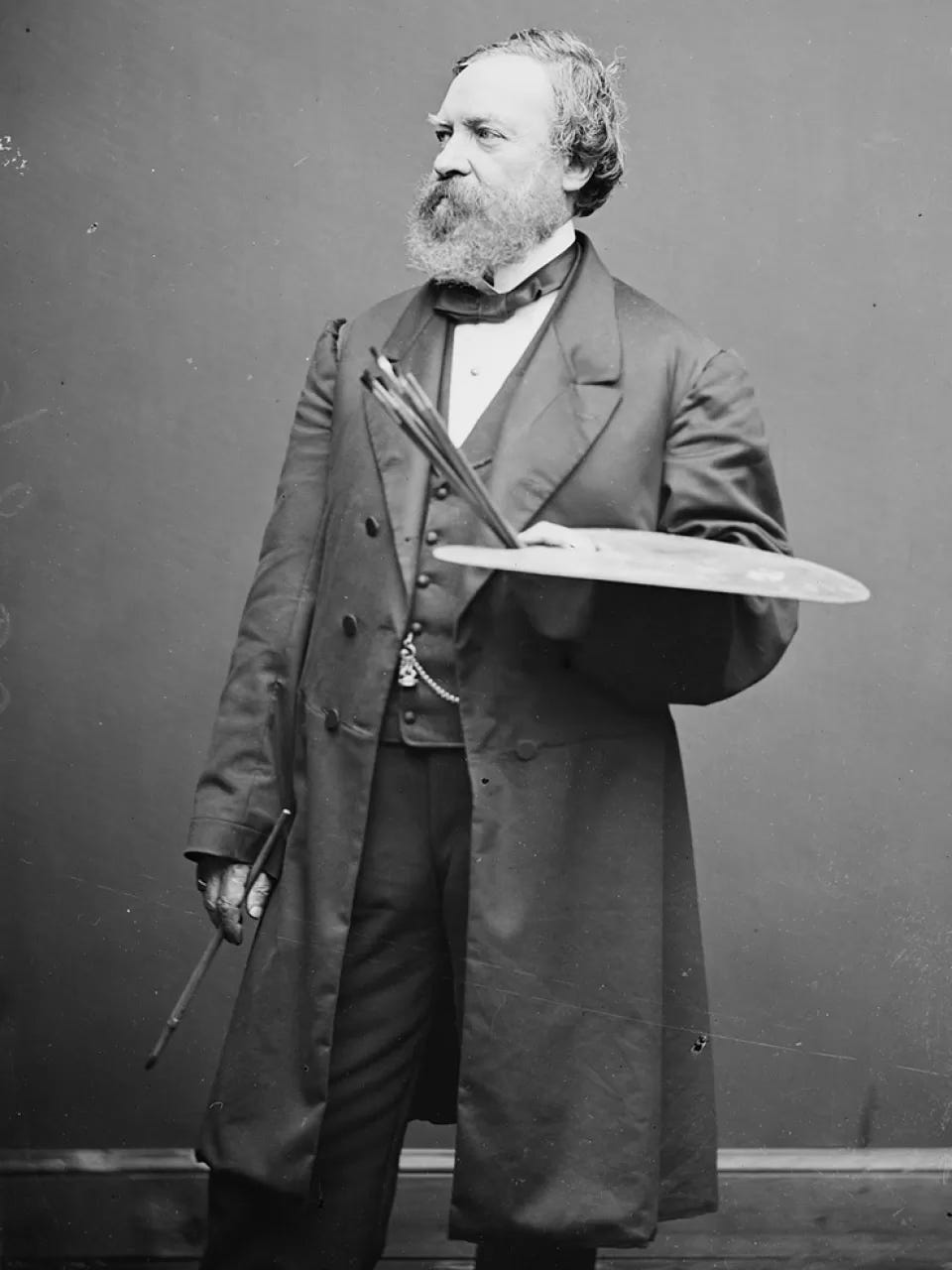

Brumidi was no “invasion” force of anything other than art. He was a political asylee fleeing the Papal States, a man of classical education and “cultivated tastes” who had once restored frescoes in the Vatican. When he arrived in the 1850s, the Capitol was a construction site of mud and ambition, two chambers separated by a plank, waiting for the dome that would eventually define the skyline.

It was Jefferson Davis—then a Senator and later Secretary of War, the biggest political force in the city—who oversaw the massive appropriation to expand the Capitol. Davis, complicated and contradictory, understood one thing that the current White House does not: the empire requires talent, and talent has no birthright. “It matters not where an artist is born,” the engineer Montgomery Meigs wrote in Brumidi’s defense. “That is beyond his control.”

But the Nativists, the “Know-Nothings” of 1854, controlled the streets and the committee rooms. They were the spiritual ancestors of today’s West Wing ideologues. They looked at Brumidi’s work—the “Loggia of Raphael” brought to the Potomac—and saw only a threat. The New York Tribune derided him as a “dauber of speckled men,” and critics in the House called his work “tawdry and gaudy,” furious that “foreign hirelings” were taking jobs from American painters who, quite frankly, didn’t know how to paint a fresco that wouldn’t peel in a week.

They formed commissions to stop him. They froze his pay. For six months in 1860, Brumidi painted the corridors of power without a paycheck, surviving on debt and the solidarity of his fellow immigrant laborers—the Germans, the French, the Italians who made up the “crowd of sixty or seventy” artisans under his command. He possessed, as his contemporaries noted, a “great good heart,” giving freely to his countrymen in distress, paying for their medicine and their funerals, even as the nativist press tried to bury his reputation.

Brumidi survived the Know-Nothings. The Art Commission that was created to destroy him was abolished; the critics lost their seats or their relevance; the Civil War came and went. Brumidi kept painting. He died poor, but he left us the Rotunda.

That same resilience was on display all week, not in the humid swamp of D.C., but in the bone-cracking cold of Minneapolis. When the wind chill hit forty below, the city did not hunker down; it stood up. A massive General Strike paralyzed the metro area, a collective refusal to normalize the “secret police” tactics being piloted by the administration.

At the Minneapolis airport this month, the resistance took on a moral clarity that would have silenced a cathedral. One hundred priests, vestments whipping in the freezing wind, blocked the tarmac to stop Delta Airlines from facilitating ICE deportation flights. They were arrested, one by one, a procession of conscience against the banality of contracted evil. These are not the actions of a defeated populace. They are the friction that wears down the machine.

Stephen Miller is betting on exhaustion. He is banking on the idea that the American people will eventually accept the purge of their neighbors as the cost of doing business. But he misreads the room, just as the Know-Nothings misread the 1850s. The “brainrot” of the nativist movement is loud, but it is historically brittle.

Adversity is the medium in which the immigrant works. Brumidi painted his masterpieces by candlelight when the funds for gas were cut. He painted through the insults, through the xenophobia, through the broken English he spoke until his dying day. He knew that the paint dries, the art remains, and the critics eventually become nothing more than footnotes in the tour guide’s script.

The shadow presidency is formidable, and the pain it inflicts is real. But the people shivering on the picket lines in Minnesota and the immigrants painting the next chapter of this country share a secret that Miller will never understand: You can delay the work, you can refuse to pay for it, you can even arrest the artists. But you cannot stop the creation of a nation that belongs to everyone. The dome is already painted. We just have to keep the roof from caving in while I paint the characters beneath it.